Nov 5, 2025

| Shamsuddin Illius

On the outskirts of Gazipur, north of Dhaka, bulldozers roar across the sprawling landscape of the Kaliakoir Hi-Tech Park – Bangladesh’s flagship technology zone.

Steel and concrete frames towered over the clay; cables snaked through trenches; and the air hummed with the promise of digital data sovereignty. Local and foreign firms, building data centers and computing power to enable artificial intelligence (AI), rising rapidly across the park.

Here, the US-based Osiris Group, in partnership with Jatra International, is investing $200 million to build a Tier-IV data center — a state-of-the-art facility designed to handle massive volumes of digital information.

Rows of server racks are being set up to process everything from e-commerce and bank transactions to data streaming and AI computation. Meanwhile, RedDot Digital Ltd, a 100% subsidiary of Robi Axiata PLC, which is owned by Malaysia-based Axiata and India’s Bharti Airtel, has also joined the race.

RedDot Digital said, “We aim to support the Government of Bangladesh in meeting its digital goals by offering cutting-edge, home-grown, cost-optimized IT applications, Cloud DC, IoT solutions, among others.”

In 2024, the company established the country’s first commercial Tier-IV data centre in Jashore. Local players, such as Intercloud Data Center, AyAl Corp Limited, and Novocom are under construction, while at least three more foreign investors – including one from the USA – are in the pipeline to invest in data centers at the park, according to the Bangladesh Hi-Tech Park Authority (BHTPA).

Earlier, India’s Hiranandani Group planned two data centers with a combined capacity of 28.8 MW, while Saudi Arabia’s DataVolt and India’s Yotta Infrastructure had pledged over $290 million in investments.However, one month after the regime change following the student uprising in August 2024, the contracts were cancelled due to slow progress.

As data center investments surge across South and Southeast Asia, Bangladesh too is witnessing the same momentum. It is estimated that Bangladesh already has a latent data center requirement of around 200 MW, projected to grow to over 500 MW by 2030. Expected revenue in the data center market is projected to reach US$679.67 million in 2025.

Government officials say proposals for new data centers and computing infrastructure are being lined up across the country’s seven high-tech parks, reflecting Bangladesh’s growing ambition to position itself as a regional digital hub. At Kaliakoir, operational data centers now include the state-owned data centre run by Bangladesh Data Center Company Limited (BDCCL), established at a cost of Tk 1,600 crore and spanning 200,000 square feet. It features 604 rack spaces in four featuring case halls. It is powered by eight 2.5 MW generators, with a total data capacity of 4 MW.

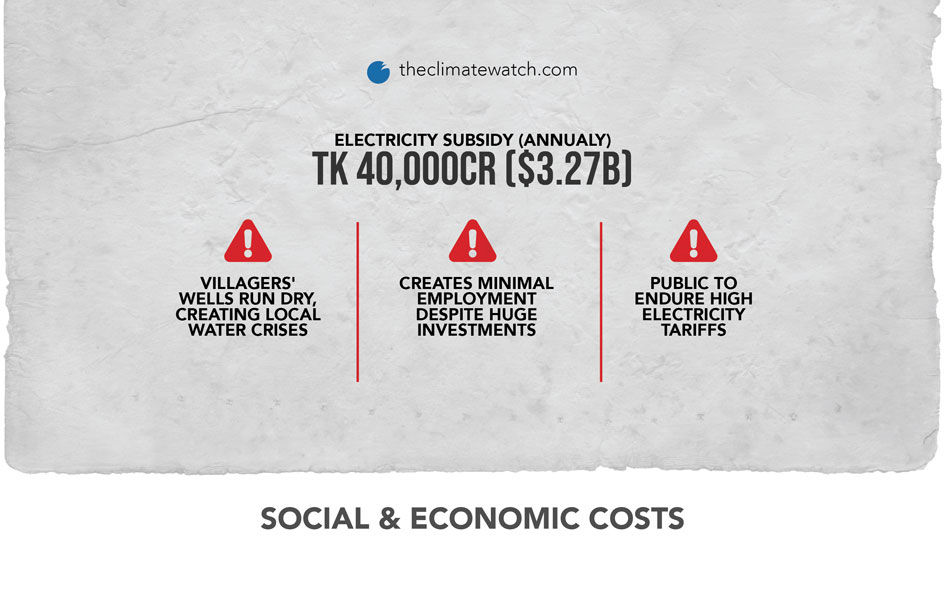

However, only 69 jobs were created. The Climate Watch investigation found one-year power of power use of this data center from July 2024 to June 2025 shows that monthly average use is 7,55,750 KWh. According to study, it is the use of around 8,000-10,000 rural households of Bangladesh.

In the same park the Felicity IDC Data Center, with a 5 MW capacity, is also operational, which is also dependent on grid power. But behind the shining hype of data centers, a far more sobering equation is unfolding.

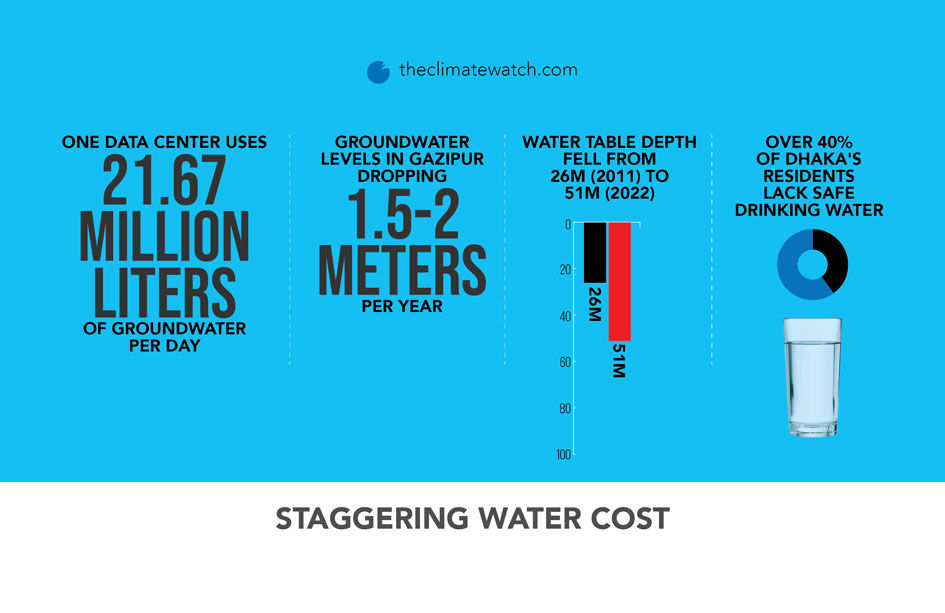

The single facility of Osiris Group alone will consume 20 megawatts of electricity daily and require a staggering 21.67 million liters of groundwater per day for cooling once operational, according to BHTPA data.

To ensure uninterrupted power, a 20 MW substation is under construction, while two 10 MW substations have already been completed, said the BHTPA. The authority has received investment proposals from 79 companies in different categories – mostly digital device manufacturers producing components such as Optical Network Units, Optical Network Terminals, Optical Line Terminals, smartphones, cameras, and AI-based electronic service devices.

BHTPA officials said they would need around 120 MW of electricity solely for this park, which is currently dependent only on groundwater. Several foreign firms are investing in Bangladesh, partnering with local entities to build new facilities. In January this year, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) announced plans to build a data center in Chattogram in partnership with the government.

Bangladesh has seen a rise in both local and foreign investment in data centers, driven by increasing digital demand across sectors like banking, telecom, and education.

Several companies have already developed Tier-III and Tier-IV facilities, offering secure, scalable storage and cloud services. However, none of them disclose their water or electricity consumption.

Experts say that while data sovereignty requires domestic data centers, it must be remembered that developed countries are increasingly relocating these energy-intensive facilities to the Global South. They warn that for a country producing only 2% of its power from clean sources, where millions still live with rolling blackouts lasting 2–10 hours daily (depending on season and region), and where industries suffer from acute water crises and groundwater depletion, this boom of data centers signals a deep contradiction at the heart of Bangladesh’s digital revolution.

From ‘Digital Bangladesh’ to Data Hub

During the 2008 national polls, the Bangladesh Awami League, one of the largest political parties – which later came to power – launched the “Digital Bangladesh” campaign as part of its election manifesto. The government has since aggressively pursued technology-led modernization, building tech zones, software parks, and data centers. Authorities hailed it as a success – a symbol of business advancement and national data storage sovereignty.

But behind the glass facades lies a less-publicized reality – these centers consume hundreds of megawatts of power daily and use millions of liters of groundwater, exacerbating environmental and climate pressures. Although Bangladesh is one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries, still struggling for green energy and water security, the BHTPA has approved dozens of facilities nationwide — yet cannot provide clear data on their electricity or water consumption. The Climate Watch sought data and requested site visits from several organizations but received no response.

According to the Ministry of Posts, Telecommunications and ICT, Bangladesh currently hosts 48 data centers, including 22 public and 26 private ones. However, despite repeated requests, officials could not confirm their total power or water usage.

These include Grameenphone’s Super Core Data Center in Sylhet – a 4 MW facility developed in collaboration with Norway’s Telenor – as well as Felicity IDC and Red Data Centers, among others.

Digital gold rush on fragile ground

Faiz Ahmad Taiyeb said they are in discussions with three more international companies, including one from the USA, which has shown interest in investing in Bangladesh, though he declined to disclose names. Currently, most of the nation’s data traffic still passes through Singaporean servers. By building local storage capacity, the government hopes to keep data – and dollars – within its borders. But this ambition collides with harsh ecological limits.

The Kaliakoir Hi-Tech Park, for instance, has a current capacity of just 7 MW but requires a staggering 120 MW to meet future expansion plans. Combined, the Kaliakoir and Sylhet parks alone will need around 180 MW of electricity daily. For comparison, that is more power than many entire districts consume. Bangladesh’s power sector emissions have grown nearly eight-fold in the last two decades, as 98% of its power still comes from fossil fuels and coal. Every new data center deepens the nation’s carbon footprint.

Globally, data centers are known as “the factories of the digital age.” They are energy-intensive, running around the clock to keep servers cool and secure. But in Bangladesh – one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries – the costs are magnified. Each megawatt of data-center capacity requires an estimated 25 cubic meters of cooling water per day.

According to the Data Center Journal, Bangladesh has 16 data centers in Dhaka alone. In a city where over 40% of residents lack access to safe drinking water, this is an alarming trade-off. The Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (WASA), burdened by $1.66 billion in foreign loans, struggles to meet the needs of the city’s 24 million residents. Chattogram WASA, too, reels under $525 million in debt while serving barely six million people.

Yet both continue supplying industrial users, including data centers – sometimes at subsidized rates – while residential consumers face rationing or salinity-related service suspensions. That means the combined facilities in Gazipur and Dhaka could collectively extract hundreds of millions of liters of groundwater daily, accelerating depletion in already-stressed aquifers.

“Water levels here are dropping fast,” said Dr Anwar Zahid, adjunct faculty at the Department of Disaster Science and Climate Resilience and the Department of Soil, Water and Environment, University of Dhaka. “In 2011, the depth was 26 meters. By 2022, it reached 51 meters. Every year, it’s sinking further.”

Dr Zahid, who formerly served as director of the Groundwater Resources Department of the Bangladesh Water Development Board, warned, “Gazipur is a water-stressed area where groundwater is depleting by 1.5 to 2 meters every year. “Allowing more water-intensive industries here will lead to an environmental disaster.”

Citing the Bangladesh Water Act, 2013, he noted, “The highest priority for both groundwater and surface water is given to drinking, hygiene, and sanitation. This right takes precedence over all other uses. Industrial use ranks much lower – seventh on the priority list.

“Permitting industries to extract groundwater at the expense of this first priority is a violation of the law. Yet, the government continues to issue such permissions.” He suggested that industries should be established near rivers and other water bodies where surface water is available, helping to recharge groundwater.

M Zakir Hossain Khan, chief executive of think-tank Change Initiative and editor-in-chief of Nature Insights, said, “Bangladesh’s position within the Bengal Delta is defined by an ecosystem where rivers, soil, forests, and people are inseparable. “Economic planning and governance must therefore align with the delta’s natural flow and regenerative capacity. In this region, nature is not merely a resource, rather the fundamentals of existence and economic prosperity.”

He emphasized, “Priority must be given to nature, expanding renewable energy, conserving groundwater, and managing high-stress zones in Rajshahi, Chapainawabganj, Naogaon, and Chattogram and other areas. “To ensure sustainability, Bangladesh should adopt a holistic legal framework for data-center governance that upholds nature justice and advances nature-led energy sovereignty.”

Hasan Mehedi, Chief Executive of CLEAN (Coastal Livelihood and Environmental Action Network), said that Bangladesh pays several hundred million dollars yearly to foreign data centers for data management – a figure that is rapidly increasing. “For data sovereignty, we need domestic data centers,” he said, “but unregulated centers are becoming more concerning. We must not approve any data center without renewable energy. These data centers consume huge amounts of water, mostly from groundwater or government water supply.” “We are a country where groundwater is depleting every day. We must formulate a guideline and law for reusing and recycling water and stop lifting groundwater,” Mehedi stressed.

Groundwater depletion: A silent crisis

During a recent visit to Kaliakoir Hi-Tech Park, it was observed that the authority is developing a groundwater-based supply system. Several deep tube wells have already been installed to supply groundwater.

There is no official water supply, so all entities depend on groundwater extraction. Shahriar Kabir, assistant engineer of the project, told The Climate Watch, “The authority has established three water pump houses. Each pump can extract 1.7 lakh liters of water per hour. These pumps will supply water to the industrial plots. “Besides these, the industries have their own pumps and water reservoirs.”

In 2023, Bangladesh’s groundwater level in many urban zones dropped to its lowest in 30 years. Studies by the Institute of Water Modelling (IWM) show that water tables in Dhaka have fallen by more than 3 meters per year in some locations. Every new borehole deepens the problem. Around Kaliakoir, villagers already report that hand pumps run dry during dry months.

“We used to get water at 150 feet,” said 45-year-old farmer Harun Mia from Mirzapur, near the Hi-Tech Park. “Now the pump doesn’t work even at 300 feet. And we are told the new data centers will use thousands of liters every minute.”

This unchecked extraction also risks salinity intrusion in coastal aquifers and subsidence of urban areas – both potentially irreversible, experts warn. Dr Anwar Zahid, Director of the Groundwater Resources Department, said that the high amount of groundwater extraction in the park could cause a severe water crisis for the residents of surrounding villages.

The paradox of progress

Bangladesh is not alone in facing this dilemma. Globally, the cloud’s carbon shadow is expanding. Data centers now account for nearly 3% of global electricity demand and emit as much CO₂ as the aviation industry.

Yet, in Bangladesh, the paradox is sharper. The same country where millions still endure at least 2–4 hours of power cuts daily and industries shut down due to gas shortages is now allocating scarce energy and water to digital infrastructure.

Bangladesh’s renewable energy share remains just 2%, despite repeated pledges to reach 10% by 2030. Meanwhile, the government continues to subsidize coal and imported LNG, with new plants under construction in Matarbari and Payra. Dr Ahmad Kamruzzaman Majumder, professor of Environmental Science at Stamford University Bangladesh, said, “The developed world is shifting energy-intensive data centers to the Global South, where the strain and carbon footprint fall on us.

“Big giants – Google, Amazon – set up their data centers here.” “If we continue fueling data centers with fossil energy and groundwater,” he warned, “we’re digitizing disaster.”

Unregulated and unaccountable

Unlike Singapore or the European Union, Bangladesh has no mandatory disclosure policy for data centers’ environmental footprints. There are no requirements to report energy efficiency, water consumption, or carbon emissions. The BHTPA confirms that while companies must obtain environmental clearance, “specific water and power metrics are not publicly disclosed.”

Even the National Data Center, operated by the BDCCL, does not release its energy or water data. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports for most new projects remain inaccessible. During a recent visit, the correspondent was not allowed to enter the data center.

However, access was granted to a 5 MW facility, Felicity IDC Data Center, which has taken some environmental measures. Concerned about energy and water consumption, the data center uses an air-cooling chiller system that recirculates the same water for cooling. It has also installed a 4 KW solar plant to transition towards a greener operation. Himan Mazumder, manager (Building Management System), Felicity IDC Internet Data Center said,, said, “It is our company’s concern that we want to reduce water use and dependency on fossil fuel electricity.

“We have installed air-cooling chillers and two solar plants that will supply half of our total power requirement.”

Growing hunger for electricity, gas

The World Energy Council (WEC) ranked Bangladesh among the leading countries in terms of energy equity, with its score increasing fourfold between 2000 and 2023. This progress stemmed largely from the nation’s expanded power generation capacity.

Yet, the high cost of electricity production led the government to raise tariffs on four occasions between January 2023 and March 2024, driving up retail electricity prices by over 20%. Despite these adjustments, Bangladesh still faced power outages on at least 23 separate days during the first nine months of the 2023–24 fiscal year.

In addition, the persistent shortage of natural gas – around 1,000 million cubic feet per day (MMcfd) below the 4,000 MMcfd demand – has compelled many industries to scale back their operations. Every year, Bangladesh provides around Tk40,000 crore ($3.27 billion) in subsidy to the electricity sector. In fiscal year 2022-2023, Bangladesh provided a subsidy of Tk39,350 crore ($3.22 billion) to this sector.

For 2023-2024, this subsidy stood at Tk 38,289 crore ($3.13 billion), which is 5.02% of the total national budget. This public taxpayer money is being diverted to unregulated data centers.

What the government says

Each gigabyte of data downloaded consumes roughly 200 liters of freshwater, yet this invisible cost often goes unnoticed. People find it easier to imagine environmental damage happening “somewhere else.” In the Asia-Pacific region, many assume that because Big Tech giants operate mainly from the West – particularly North America – the ecological consequences of their activities are confined there, ignoring the growing environmental burden quietly shifting to developing nations.

Faiz Ahmad Taiyeb, special assistant to the chief adviser of Bangladesh who oversees the ministry as state minister, told The Climate Watch, “We are concerned about the business and environmental sustainability of data centers.“For that reason, the government is not making data localization 100% compulsory. If we do, we will have to supply them energy, electricity, and water – which will be a burden for the country.”

“We are opting for a trade-off where we will not lose our data sovereignty but will still be able to secure data. We are planning to offer a balanced cloud policy where companies will inform the government about what type of data they are sending abroad,” he said.

“Several foreign companies have already shown interest in establishing data centers in Bangladesh, and the government is considering their proposals, though we are still at an early stage of communication,” he added.

However, the government has yet to formulate any policy for the environmental sustainability of data centers. When contacted, Syeda Rizwana Hasan, adviser to the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change, declined to comment on the issue.

Rakibul Islam, project director of Kaliakoir Hi-Tech City, said, “Data centers are highly electricity and water-consuming facilities. Though they involve huge investment, they create minimal employment opportunities. “Initially, we could not assess the high demand for electricity by the data centers. We have only 10 MW capacity, while a single data center requires 20 MW itself. We asked the companies (Jatra International) building data centers to arrange their own electricity.” “Now we have decided against accommodating any more data centers in the park,” he added.

Are there any solutions?

Experts emphasize that data centers must rely on green energy and surface water instead of groundwater. Bangladesh, they warn, must not fall into the trap set by developed countries – allowing unregulated, resource-hungry data centers to operate unchecked. They call for strict guidelines and legal frameworks to ensure responsible operation, resource reuse, and renewable power integration before approving future projects.

Commenting on the issue, climate scientist Prof AKM Saiful Islam from the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET), said, “Bangladesh should pursue a just energy transition, investing in renewable power and rural electrification alongside its digital growth to ensure that data sovereignty does not deepen inequality.” Prof Islam, who has contributed to multiple IPCC reports, concluded, “True progress lies in powering both people and processors, linking digital advancement with clean, inclusive, and equitable energy access.”

News Link: DIGITAL DREAMS, PARCHED REALITY: The hidden cost of Bangladesh’s data industry gold rush